Episode Details

Back to Episodes

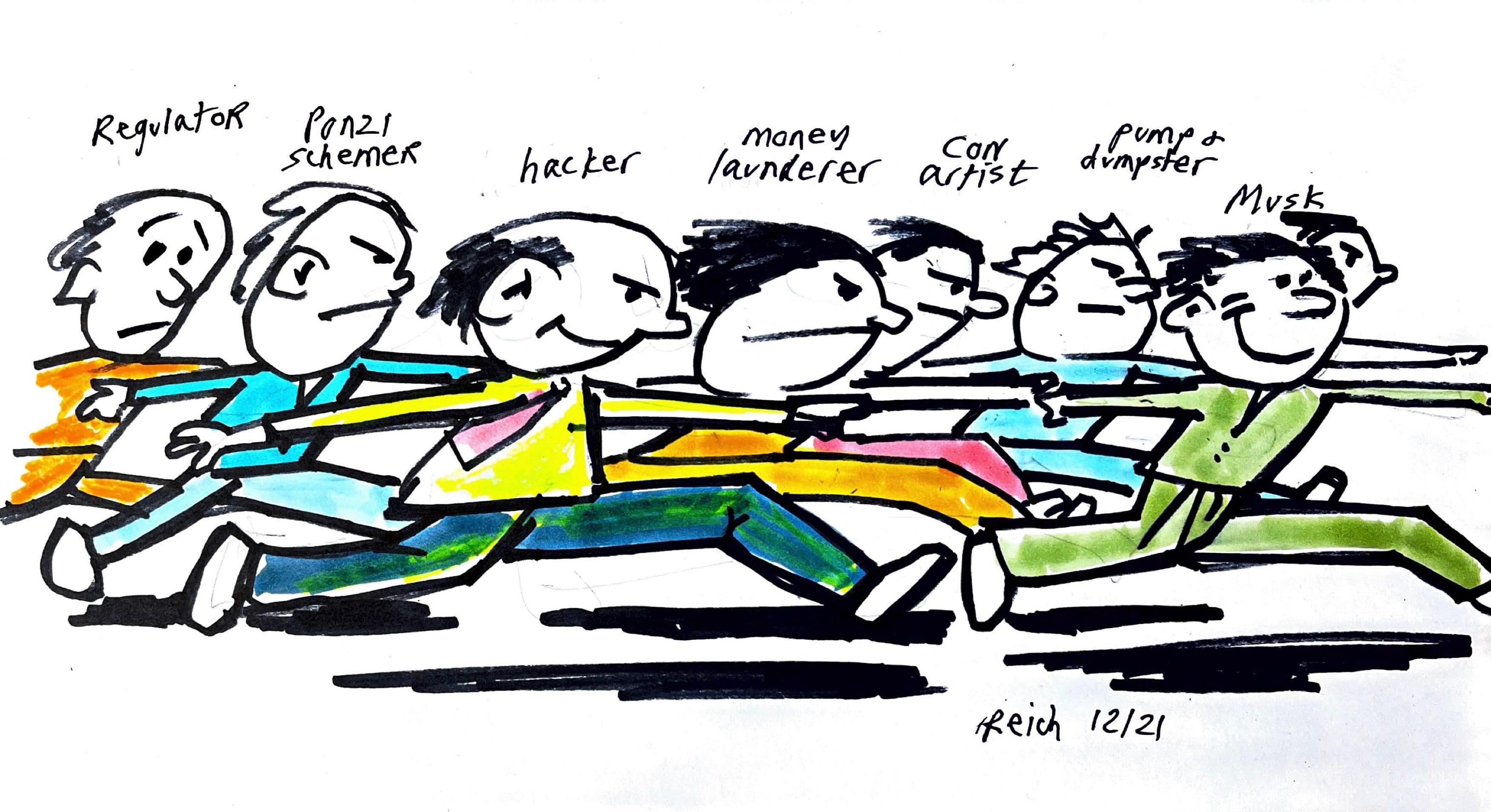

What the crypto crash tells us

Description

Last Sunday night, as cryptocurrency prices plummeted, Celsius Network — an experimental cryptocurrency bank with more than one million customers that has emerged as a leader in the murky world of decentralized finance, or DeFi — announced it was freezing withdrawals “due to extreme market conditions.”

Earlier this week, Bitcoin dropped 15 percent over 24 hours to its lowest value since December 2020, and Ether, the second-most valuable cryptocurrency, fell about 16 percent. Last month, TerraUSD, a stablecoin — a system that was supposed to perform a lot like a conventional bank account but was backed only by a cryptocurrency called Luna — collapsed, losing 97 percent of its value in just 24 hours, apparently destroying some investors’ life savings. The implosion helped trigger a crypto meltdown that erased $300 billion in value across the market.

These crypto crashes have fueled worries that the complex and murky crypto banking and lending projects known as DeFi are on the brink of ruin.

Eighty nine years ago today the Banking Act of 1933 — also known as the Glass-Steagall Act — was signed into law by Franklin D. Roosevelt. It separated commercial banking from investment banking — Main Street from Wall Street — in order to protect people who entrusted their savings to commercial banks from having their money gambled away. Glass-Steagall’s larger purpose was to put an end to the giant Ponzi scheme that had overtaken the American economy in the 1920s and led to the Great Crash of 1929.

Americans had been getting rich by speculating on shares of stock and various sorts of exotica (roughly analogous to crypto) as other investors followed them into these risky assets — pushing their values ever upwards. But at some point Ponzi schemes topple of their own weight. When the toppling occurred in 1929, it plunged the nation and the world into a Great Depression. The Glass-Steagall Act was a means of restoring stability.

It takes a full generation to forget a financial trauma and allow forces that caused it to repeat their havoc.

By the mid-1980s, as the stock market soared, speculators noticed they could make lots more money if they could gamble with other people’s money, as speculators did in the 1920s. They pushed Congress to deregulate Wall Street, arguing that the United States financial sector would otherwise lose its competitive standing relative to other financial centers around the world.

In 1999, after Sandy Weill’s Travelers Insurance Company merged with with Citicorp, and Weill personally lobbied Clinton (and Clinton’s Treasury secretary Robert Rubin), Clinton and Congress agreed to ditch what remained of Glass-Steagall. Supporters hailed the move as a long-overdue demise of a Depression-era relic. Critics (including yours truly) predicted it would release a monster. The critics were proven correct. With Glass-Steagall’s repeal, the American economy once again became a betting parlor. (Not incidentally, shortly after Glass-Steagall was repealed, Sandy Weill recruited Robert Rubin to be chair of Citigroup’s executive committee and, briefly, chair of its board of directors.)

Inevitably, Wall Street suffered another near-death experience from excessive gambling. Its Ponzi schemes began toppling in 2008, just as they had in 1929. The difference was that the U.S. government bailed out the biggest banks and financial institutions, with the result that the Great Recession of 2008-09 wasn’t nearly as bad as the Great Depression of the 1930s. Still, millions of Americans lost their jobs, their savings, and their homes (and not a single banking executive went to jail). In the wake of the 2008