Episode Details

Back to Episodes

The curse of financial entrepreneurship

Description

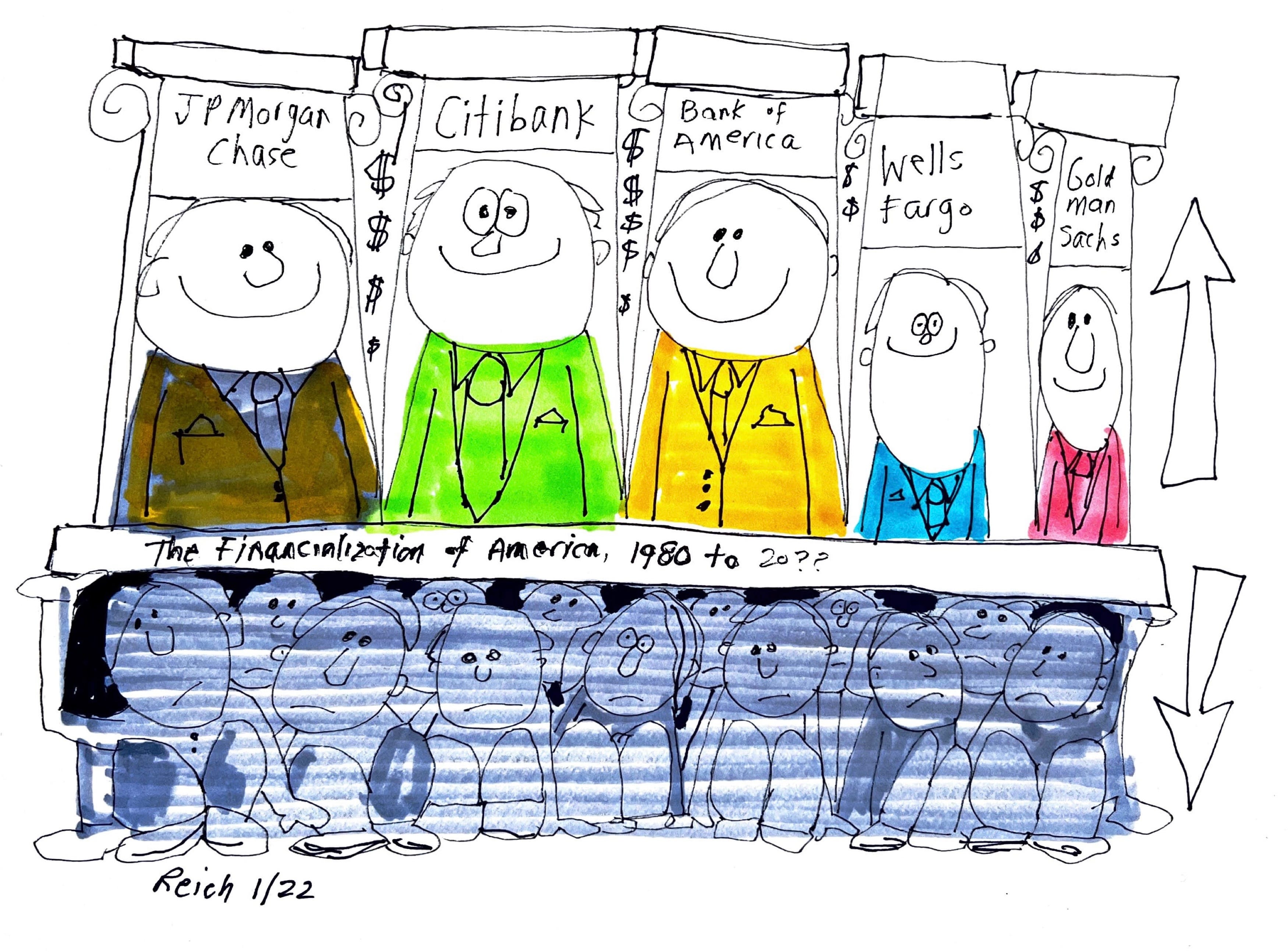

Wall Street may be having a bad week, but top bankers are doing wonderfully well. After a blockbuster year, the five biggest Wall Street banks just paid out $142 billion in bonuses and compensation for 2021. This was $18 billion more than in 2020. JPMorgan Chase reported record profits, and Citigroup’s annual profit more than doubled. Let me remind you (as if you need reminding) that 2020 and 2021 were not exactly blockbuster years for the rest of America.

In the first three decades after World War II, American companies made money by making things, selling them at a profit, and investing the profits in additional productive capacity. This helped create the largest middle class the world had ever seen. In those years, the financial sector accounted for 15 percent of U.S. corporate profits.

Then something happened. By the mid-1980s, the financial sector claimed 30 percent of corporate profits. By 2001, 40 percent — more than four times the profits made in all U.S. manufacturing.

Why this dramatic change? Indulge me a moment as I quote from a New York Times op-ed I wrote more than forty years ago (May 23, 1980):

The paper entrepreneurs are winning out over the product entrepreneurs.

Paper entrepreneurs – trained in law, finance, accountancy – manipulate complex systems of rules and numbers. They innovate by using the systems in novel ways: establishing joint ventures, consortiums, holding companies, mutual funds; finding companies to acquire, “white knights” to be acquired by, commodity futures to invest in, tax shelters to hide in; engaging in proxy fights, tender offers, antitrust suits, stock splits, spinoffs, divestitures; buying and selling notes, bonds, convertible debentures, sinking-fund debentures; obtaining government subsidies, loan guarantees, tax breaks, contracts, licenses, quotas, price supports, bailouts; going private, going public, going bankrupt.

Product entrepreneurs – engineers, inventors, production managers, marketers, owners of small businesses – produce goods and services people want. They innovate by creating better products at less cost.

Our economic system needs both. Paper entrepreneurs ensure that capital is allocated efficiently among product entrepreneurs. But paper entrepreneurs do not directly enlarge the economic pie. They only arrange and divide the slices. They provide nothing of tangible use. For an economy to maintain its health, entrepreneurial rewards should flow primarily to product, not paper.

Yet paper entrepreneurialism is on the rise. It dominates the leadership of our largest corporations. It guides government departments, legislatures, agencies, public utilities. It stimulates platoons of lawyers and financiers.

It preoccupies some of our best minds, attracts some of our most talented graduates, embodies some of our most creative and original thinking, spurs some of our most energetic wheeling and dealing. Paper entrepreneurialism also promises the best financial rewards, the highest social status.

The ratio of paper entrepreneurialism to product entrepreneurialism in our economy – measured by total earnings flowing to each, or by the amount of news in business journals and newspapers typically devoted to each – is about 2 to 1.

Why? Our economic system has become so complex and interdependent that capital must be allocated according to symbols of productivity rather than according to productivity itself. These symbolic rules and numbers lend themselves to profitable manipulation far more readily than do the underlying processes of production.

It takes time and effort to improve product quality, exploit manufacturing efficiencies, develop distri