Episode Details

Back to Episodes

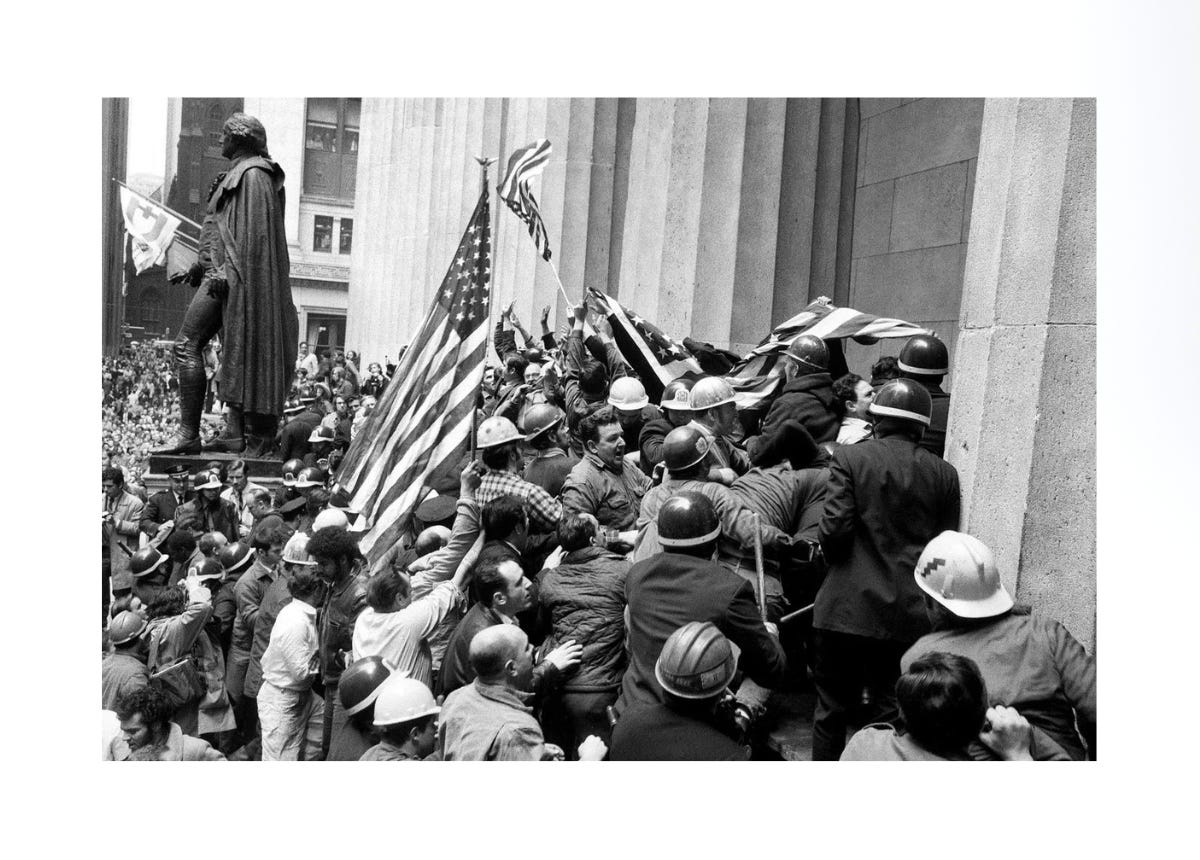

The riot that started the culture wars

Description

The culture wars now ripping through American politics — especially noticeable in these last few weeks before the midterm elections, when Trump is trying to lay the groundwork for an authoritarian takeover — arguably began on May 8, 1970 in New York City.

That day happened to be the 25th anniversary of the Allied victory over Germany in World War II. It was also weeks after Richard Nixon expanded the Vietnam War into Cambodia. And it was just four days after Ohio National Guardsmen shot dead four students during antiwar protests at Kent State University.

I recall it vividly.

On May 8, 1970, a riot broke out in New York City.

Around noon, near the intersection of Wall Street and Broad Street in Lower Manhattan, more than 400 construction workers — steamfitters, ironworkers, plumbers, and other laborers from nearby construction sites like the emerging World Trade Center — attacked around 1,000 student demonstrators (including two of my friends) protesting the Vietnam War and the May 4 Kent State shootings.

The workers carried U.S. flags and chanted “USA, All the way” and “America, love it or leave it.” They chased the students through the streets — attacking those who looked like hippies with hard hats and weapons, including tools and steel-toe boots.

I heard about it when several friends from New York who were active in the anti-Vietnam War movement phoned me later that day. To characterize them as upset understates their emotions.

As David Paul Kuhn reports in The Hardhat Riot, the police did little to stop the mayhem. Some even egged on the thuggery. When a group of hardhats moved menacingly toward a Wall Street plaza, a patrolman shouted: “Give ’em hell, boys. Give ’em one for me!”

The workers then stormed a barely-protected City Hall where the mayor’s staff, to the hardhats’ rage, had lowered the flag in honor of the Kent State dead. They pushed their way to the top of the steps and attempted to gain entrance, chanting “Hey, hey, whatcha say? We support the USA!”

Fearing the mob would break in, a person from the mayor’s staff raised the flag.

It was a small precursor to the attack on the U.S. Capitol more than a half-century later.

The workers ripped down the Red Cross flag that was hanging at nearby Trinity Church because they associated the flag with the anti-war protests. They stormed the newly built main Pace University building, smashing lobby windows and beating students and professors with their tools.

More than 100 people were wounded. The typical victim was a 22-year-old white male college student, though one in four was female. Seven police officers were also hurt. Most of the injured required hospital treatment. Six people were arrested, but only one construction worker.

My friends escaped injury but they were traumatized. I remember them describing the rioting construction workers as a “pack of animals.”

The hardhat riot had immediate political consequences. Richard Nixon exploited it for political advantage. It was the first salvo in America’s culture wars.

Nixon’s chief of staff H.R. Haldeman wrote in his diary: “The college demonstrators have overplayed their hands, evidence is the blue-collar group rising up against them, and [the] president can mobilize them.”

Patrick Buchanan, then a Nixon aide, wrote in a memo to his boss, saying “blue-collar Americans” are “our people now.”

Peter Brennan, then president of the Building and Construction Trades Council of Greater New York, claimed “the unions had nothing to do with” it — although just before the riot, Brennan had held a rally of construction workers to show support for Nixon’s Vietnam policies.

Brennan explained that workers were “fed up” with violence and flag desecration by anti-war demonstrators.

At Nixon’s invitation, Brennan then led a delegation of 22 union leaders,